An Environmental, Social, and Governance Program for Corporate Real Estate and Facilities Departments

From Corporate Real Estate Journal Volume 10, Number 3, pp. 295–303 © Henry Stewart Publications

Received (in revised form): 11th January, 2021

Colette Temmink

Chief Strategy and Product Officer, Blue Skyre, USA

David Flynn

Chief Operating Officer, Blue Skyre, USA

Colette Temmink, serves as Chief Strategy and Product Officer at Blue Skyre IBE (BSI). Colette oversees the strategy, product development and quality being delivered to customers to enhance their real estate performance. Prior to cofounding BSI, Colette was president of property services at Eden where she was responsible for enabling companies to seamlessly run and scale their real estate portfolios, using technology. Previously, Colette was the global head of integrated facilities management (IFM) for Cushman & Wakefield. She also served as senior vice president and chief administration officer at Apollo Education Group and held global real estate executive roles at Boeing and Oracle. Colette is a global board member of the International Facilities Management Association (IFMA) and her professional affiliations include Counselor of Real Estate (CRE®), Fellow Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (FRICS), Certified Property Manager (CPM), Masters of Corporate Real Estate (MCR), Senior Leader of Corporate Real Estate (SLCR) and Certified Facility Manager (CFM).

David Flynn, is the COO of Blue Skyre IBE, LLC (BSI). Prior to BSI, he held executive roles leading facility management and property management at JLL, Grubb & Ellis and WeWork. He held leadership roles on the real estate asset management teams at Citibank and UBS. David’s experience includes facilities, CBD and suburban investment properties and debt port- folios. The portfolios were comprised of a variety of asset types including office, retail, industrial, multifamily and hotel properties. Responsibilities included P&L accountability, leasing, operations, dispositions, financing, refinancing, leading outsourced teams, risk management, client relations, operational excellence, data standards and compliance. David is a Certified Property Manager and a member of the Institute of Real Estate of Management (IREM), a member of the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (MRICS), a member of International Facility Management Association (IFMA) and CoreNet.

ABSTRACT

A favorable environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating is of rising importance to companies because of expanding awareness and the growing acceptance among large investors that a robust ESG program translates into strong market performance. Corporate real estate (CRE) intersects with many of the elements affecting a company’s ESG objectives and plays a significant role in helping it design and achieve its ESG objectives. There is a lack of clarity among rating systems and users have difficulty correlating ratings to a CRE program. While the make-up of a CRE program for environmental is well developed, there are great opportunities for advancement in the areas of societal and governance. This paper addresses current ESG program issues for CRE, offers suggestions for how CRE can approach them and provides a sample of how to develop an ESG program for real estate that will help improve the company’s performance and ultimately its market performance.

Keywords: environmental, social and governance, ESG, ESG program, facilities management, corporate real estate, sustainability

THE GROWING IMPORTANCE OF ESG

ESG is growing in importance among investors and financial institutions when making an investment decision.3 In addition, the debate about which criteria to use when evaluating an investment has a long history and inclusion of criteria beyond financial has been gaining momentum. For example, stakeholders have divested certain investments based on criteria other than pure profit. Consumers have boycotted companies and countries which have influenced social and financial change and there is certainly the impact on a company’s reputation as well as its success with attracting and retaining talent. The debate from shareholder value to creating value for stakeholders has grown in public forums over the years; however, they are not mutually exclusive. For example, ESG helps create value through the focus on stakeholder interests and this focus can increase shareholder value.4 Accordingly, demand rose in the 1990s for socially responsible funds and today this has increased to billions of dollars flowing into these investments; during the first half of 2019, these inflows exceeded 2018 by more than US$3bn.5 While the growth of ESG and its importance on investments has certainly grown, the rating systems used for ESG are not consistent. Unfortunately, a globally consistent and clear rating system does not exist. It starts with self-reporting that does not use a common standard that providers use in their ranking process.6

While this makes it challenging to compare investments purely on ESG ratings, it is also difficult for practitioners or functional departments within an organization to develop a program.

‘It has long been noted — usually with significant concern — that ESG/SRI rating and ranking organizations (and indices as well) frequently rate the same corporation’s E, S and G elements differently.’7

THE COMPLEXITY OF RANKING AN ESG PROGRAM

This paper does not attempt to rank rating companies but, rather, highlight the various ranking processes and categories needed for a broad CRE program to address the criteria of more than one. To do this, we start with the understanding of what ESG is and what CRE program and initiatives fall within the definition of ESG. While ESG can be considered as an alternative to sustainability, the definition is:

‘a set of activity or processes associated with an organization’s relationship with its ecological surroundings, its coexistence and interaction with human organisms and other populations, and its corporate system of internal controls and procedures (such as processes, customs, policies, laws, rules and regulations, etc.) to direct, administer and manage all the affairs of the organization, in order to serve the interests of stockholders and other stakeholders.’11

These sets of activities and processes have not been clearly defined for real estate in the detail needed to implement a CRE program across transactions, facilities management and/or property management. While the rating system might be unclear and the correlation to a CRE program hard to define, there is a path to an ESG program for CRE leaders. ISO 14001 (Environmental Management System) standards could be used as an outline for ESG and CSR, although not the only model that would work for all companies.12 In addition, there are no comprehensive tools or models that cover sustainability characteristics for all three ESG areas — that is, an approach that is practical for all companies.13 The more a company discloses and increases transpar- ency, however, the higher the score.14 These scores can help investors identify well-run companies (eg data is showing that com- panies focused on sustainability practices outperform peers) and potential risks (eg Sustainalytics noted governance concerns with Volkswagen and Fiat before the diesel emissions scandal).15 KPMG reported that of the world’s largest companies by revenue, 93 per cent reported on ESG.16

THE ROOTS OF ESG

This is a good place to pause and provide a brief summary of the efforts of the early advocates for socially responsible investing (SRI) and how its advocates and thought leadership influenced policy, creating a foundation upon which ESG could grow and expand. The early adopters of SRI were convinced that investing needs to take into consideration factors beyond simply increasing profits for shareholders. The basic principle of SRI can be summed up with the simple tenet: ‘Do no harm’. In the 1970s, the focus was on environmental protection.17 In the 1980s, the boundaries expanded to address bad behavior in the workplace, governance and social justice.18 By the 2000s, large investors were focusing on sustainable investing, analyzing a company’s fiduciary duty, its impact on the climate and its corporate governance, believing that if the latter was done poorly it would be harmful to the markets.19 These fostered the development of what came to be known as ESG.

A key element affecting the accuracy of disclosure is the support of the corporate executives and their willingness to create a culture of compliance by holding a company’s leadership accountable for aligning business operations with its ESG program. The confluence of these historical factors and a corporation’s commitment to meet certain ESG standards puts its brand on the line. This is where the CRE team plays an integral role. One way or another its actions and decisions affect nearly all the elements that influence ESG outcomes for the corporation. A CRE leader should be familiar with how to develop and lead an ESG program, whether they are part of an internal task team across an enterprise, contributing to developing an enterprise program, or creating one for the organization.

UNDERSTANDING THE RATING PROCESS

When beginning to outline a framework for CRE, it is helpful to first understand the rating process. There are three steps to the process:

(1) Disclosure (eg GRI and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board [SASB]);

(2) Rating (eg MSCI, Sustainalytics); and

(3) Rating reporting (selling of ESG scores).26

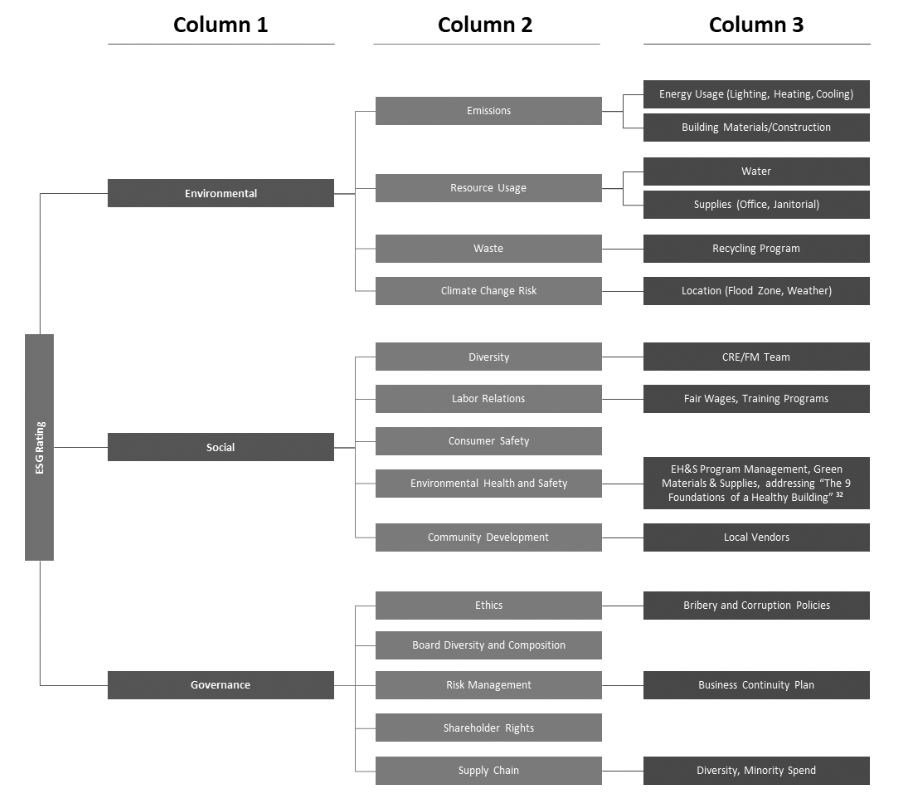

Disclosure is subsequent to action and determining the actions a CRE department can take to support the company’s ESG disclosures starts with understanding each area of ESG. The environmental scope includes how companies address waste and carbon footprint, the social scope includes the engagement of stakeholders (eg workplace health and safety, protecting customer personal data, etc.) and the governance scope minimizes fraud and threats to the roles of the board of directors.27 Many CRE departments’ sustainability programs focus on environmental areas such as emissions, utility consumption, recycling, etc.; however, little attention has been focused on social or governance areas.

When reviewing each area of Figure 1, it should be noted that the CRE potential initiatives in column 3 closely align to historical sustainability programs, specifically involving emissions, resource consumption and waste. In many cases, CRE departments have helped to lead this effort for their organizations. The largest future opportunity resonates with programs and initiatives to support the social and governance areas. This will require the collaboration of other corporate departments such as human resources (HR) and procurement. For example, procurement may contract with suppliers who deliver facilities services and ensure the contracts include policies such as anti-bribery; however, a holistic program would include ongoing performance management, additional compliance requirements, health and safety programs and tracking of minority spend.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVING MEASUREMENT, REPORTING AND COMPLIANCE

Certain categories in column 2 can be found in different ESG areas. For example, supply chain can be found in either social or governance categories. Supply chain can have an impact on many areas of ESG such as fair trade, diversity, minority spend, local protection, brand management, innovation, business continuity plans, bribery and corruption, fair wages, training pro- grammes, etc. Given that most organizations use suppliers in support of delivering and maintaining their real estate portfolio, supplier management is a particularly important criterion. This includes the compliance and performance management of the supply chain from facilities services to transactions. In addition, given many of the facilities services are provided locally on-site, this presents an opportunity for small and large locally diverse businesses. Facilities and property management are heavily reliant on local services such as electrical, janitorial, grounds maintenance, plumbing, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), etc. and this provides an opportunity for CRE departments to support their company’s ESG program and reporting.

Another area of opportunity is emissions. Buildings account for 40 per cent of emissions and reducing emissions includes the complexity of three stakeholders — the tenant, the owner and the property manager — and the fact that the real estate industry is slow to accept technology.32,33 ‘Data and technology will drive significant changes in our ability to measure, calculate and monitor ESG factors and assess their materiality and impact on long-term value creation.’34 Data and technology can help CRE departments with managing and measuring many of the initiatives for ESG, such as emissions reporting, consumption reporting (energy, water, waste, etc.), supply chain management and compliance, etc. While many CRE departments have focused on the ‘E’ of ESG and have programs and initiatives around categories such as emissions, energy consumption, etc., they do not have a holistic technology or comprehensive data program for all three areas.

Figure 1: CRE ESG actions

Source Authors/Harvard Law School Forum for Corporate Governance/Harvard Business Review

SEVEN STEPS FOR CREATING AN EFFECTIVE REAL ESTATE PROGRAM

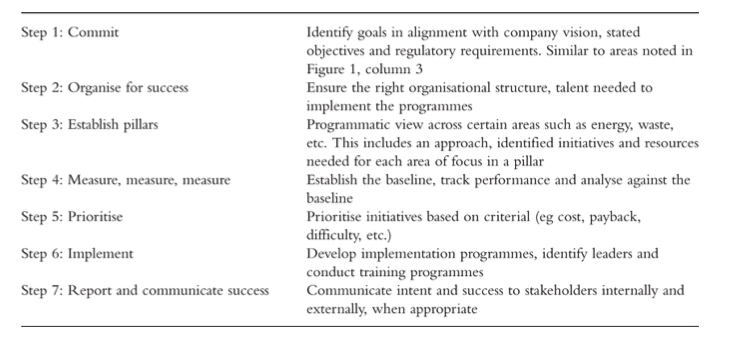

When considering developing a more detailed plan for developing an ESG program, CRE leaders may consider using established program management policies and tools, if they have already been developed and used across their company. In addition, it is helpful to have team members who understand local customs and governmental regulations on the implementation team. An alternative is to follow the seven steps outlined in Figure 2. These steps were identified to help CRE leaders develop and implement an effective real estate sustainability program,35 and can also be used to develop an ESG program. Once a company has identified which real estate programs it would like to develop based on the initiatives outlined in Figure 1, column 3, it can consider the steps outlined in Figure 2 to develop a plan.

CONCLUSION

The opportunity for a CRE department to help its company’s performance and attractiveness to investors can be correlated to its ESG initiatives. Today companies are not legally required to provide a CSR report in countries such as the US; however, they may choose to use an existing framework (US GAAP, World Intellectual Capital Initiative, etc.), to develop one for their organiZation or not at all.37 Some of the existing reporting frameworks could become the mandated regulatory standards of tomorrow.38

Despite the industry challenges involving a lack of consistent standards for reporting and ratings, CRE departments can play an important role in supporting their company’s CSR reporting and ESG program. CRE departments should evaluate their existing sustainability programs and reporting for the environmental area of ESG to ensure they have captured the categories used by rating agencies and are in alignment with their company’s strategy and goals. In addition, they should evaluate or develop programs for social and governance if they do not exist today. One of the areas that should not be overlooked is supplier management and compliance. This includes using technology to support these initiatives and programs — for example, tracking areas of legal compliance, performance and support with minority and local firms and compliance with health and safety programs.

REFERENCES

(1) Hawley, D. (2017), ‘ESG Ratings and Rankings All over the Map. What Does it Mean?’, Truvalue Labs, available at https://truvaluelabs.com/wp-content/ uploads/2017/12/ESG-Ratings-and- Rankings-All-Over-the-Map.pdf (accessed 11th January, 2021).

(2) Lo, K. Y. and Kwan, C. L. (2017), ‘The Effect of Environmental, Social, Governance and Sustainability Initiatives on Stock Value – Examining Market Response to Initiatives Undertaken by Listed Companies, Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management, Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 606–619.

(3) Bell, C. and Voorhees, J. (2020), ‘Using Standards as a Framework for Environmental and Social Governance’, Natural Resources & Environment, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 41–45.

(4) Hicks, C. (November 2020), ‘What Is Shareholder Value?’, US News Week, available at https://money.usnews.com/ investing/investing-101/articles/what-is- shareholder-value (accessed 4th January, 2021).

(5) Schanzenbach, M. M. and Sitkoff, R. H. (2020), ‘Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee’, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 72, No. 2, pp. 381–454.

(6) Napach, B. (August 2018), ‘Understanding ESG Ratings: A Brief Primer From Celent’, Think Advisor, available at https://www.thinkadvisor. com/2018/08/06/understanding- esg-ratings-a-brief-primer-from-cele/ (accessed 7th November, 2020).

(7) Ibid., note 1, p. 3.

(8) Ibid., note 1, p. 3.

(9) Ibid., note 1.

(10) Ibid., note 1.

(11) Whitelock, V. G. (2019), ‘Multidimensional environmental social governance sustainability framework: Integration, using a purchasing, operations, and supply chain management context’, Sustainable Development, Vol. 27, No. 5, pp. 923–931.

(12) Ibid., note 3.

(13) Ibid., note 10.

(14) Spitzer, S. W. and Mandyck, J. (May 2019), ‘What Boards Need to Know About Sustainability Ratings’, Harvard Business Review, available at https://hbr. org/2019/05/what-boards-need-to-know- about-sustainability-ratings (accessed 7th November, 2020).

(15) Ibid., note 14.

(16) KPMG (2017), ‘The Road Ahead: KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017’, available at https://home.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/campaigns/csr/pdf/CSR_Reporting_2017.pdf(go back) (accessed 11th January, 2021).

(17) Townsend, B. (2020), ‘From SRI to ESG: The origins of Socially Responsible and Sustainable Investing’, The Journal of Impact & ESG Investing Fall 2020, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 10–25, available at https:// jesg.pm-research.com/content/1/1/10 (accessed 9th December, 2020).

(18) Ibid., note 17.

(19) Ibid., note 17.

(20) Kell, G. (2018), ‘The Remarkable Rise of ESG’, Forbes, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ georgkell/2018/07/11/the-remarkable- rise-of-esg/?sh=4d3719e31695 (accessed 12th September, 2020).

(21) Ibid., note 20.

(22) Ibid., note 20.

(23) Ibid., note 20.

(24) Ibid., note 20, para 4.

(25) Ibid., note 20.

(26) Ibid., note 14.

(27) Jasni, N. S., Yusoff, H., Zain, M. M., Yusoff, N. M and Shaffee, N. S. (2019), ‘Business strategy for environmental social governance practices: Evidence from telecommunication companies in Malaysia’, Social Responsibility Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 271–289.

(28) Muñoz, T. M. J., Fernández, I. M. Á., Rivera, L. J. M. and Escrig, O. E. (2019), ‘Can environmental, social, and governance rating agencies favor business models that promote a more sustainable development?’, Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 439–452.

(29) Ibid., note 28.

(30) Huber, B. and Comstock, M. (July 2017), ‘ESG Reports and Ratings: What They Are, Why They Matter’, Harvard Law School Forum for Corporate Governance, available at https://corpgov.law.harvard. edu/2017/07/27/esg-reports-and-ratings- what-they-are-why-they-matter/ (accessed 7th November, 2020).

(31) Ibid., note 14.

(32) Colin, S. (October 2020), ‘The Growing Trend of ESG Investing in Commercial Real Estate’, Propmodo, available at http://www.propmodo.com/ the-growing-trend-of-esg-investing- in-commercial-real-estate (accessed 8th November, 2020).

(33) Foundations, ‘The 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building’, available at https://9foundations.com/ (accessed 9th December, 2020).

(34) Papadopoulos, K. and Araujo, R. (March 2020), ‘Top 10 ESG Trends for the New Decade’, Harvard Law School Forum for Corporate Governance, available at https://corpgov.law.harvard. edu/2020/03/02/top-10-esg-trends-for- the-new-decade/ (accessed 8th November, 2020).

(35) Lin, B., Romero, S., Jeffers, A. E., DeGaetano, L. and Aquilino, F. (2017), ‘Are Sustainability Rankings Consistent Across Ratings Agencies?’, CPA Journal, Vol. 87, No. 7, p. 48.

(36) Temmink, C. M. (2010), ‘A Corporate Guide to Implementing a Sustainable Real Estate Program’, Real Estate Issues, Vol. 35, available at https://www.cre.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Temmink- Final-Corporate-Guide.pdf (accessed 23rd December, 2020).

(37) Ibid., note 35.

(38) Ibid., note 34.