Back to the future: Changing business priorities have accelerated trends and are driving fundamental shifts in the structure and approach to real estate outsourcing

From Corporate Real Estate Journal Volume 10, Number 2, pp. 195–215

© Henry Stewart Publications

Received (in revised form): 22nd September, 2020

Maureen Ehrenberg

CEO, Blue Skyre, USA

Maureen Ehrenberg, FRICS, CRE, LAI is CEO of Blue Skyre, Innovating the Built Environment (BSI). An internationally recognised expert on real estate business transformation, strategic redesign for the future of work and digital facility management, Maureen serves as an adviser and board member to global organisations, investors and real estate technology providers. With more than 25 years’ experience, she has deep expertise in providing real estate advice and services to companies around the world. Before founding Blue Skyre, she was Global Head of Real Estate Operations and Strategic Services for WeWork. She has held global executive roles with JLL, CBRE and Grubb & Ellis Company. Maureen serves on the Americas Board of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) and the US Department of State Bureau of Overseas Building Operations, Industry Advisory Group (IAG). She is a management trustee for the International Union of Operating Engineers, a trustee of Roosevelt University and a member of the Real Estate Advisory Board for the New York State Teachers Retirement System (NYSTRS). Maureen has also served on the global boards of CoreNet Global, IFMA (International Facility Management Association) and OCSRE (Open Standards Consortium for Real Estate). A frequent speaker and author, Maureen has been recognised as an industry thought leader with an Innovator of the Year Award from CoreNet Global, the Chair’s Citation Award from IFMA, the Julie Devine Digital Impact and Lifetime Achievement Awards for Vision in Technology from RealComm and has received several awards and recognition for leadership and service in the real estate industry.

ABSTRACT

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) trends over recent years have driven stronger alignment of corporate real estate (CRE) management with core business transformation. Stakeholder expectations for demonstrable change are necessitating business to respond to issues at an unprecedented pace. The intense C-suite focus on purpose and accountability is demanding a reset of CRE management. Digital transformation is seen as key. ESG initiatives have caused C-suite executives to become more aware of the strategic value of CRE management. No longer viewed as a cost centre focused on cost reduction, the mandate for CRE management is to deliver value, cost efficiency, continuous improvement and innovation. Fast-paced change and the need for agility has challenged the status quo of outsourcing. New technologies, automation and shared economy models have resulted in insourcing and demand for change. The cost of inflexible and inefficient ‘self-performance’ facility management (FM) outsourcing principal contracts presents market opportunity for disruption. CRE management requires more choice and very different, flexible models. When CRE outsourcing began over 20 years ago, models varied but were highly flexible and advancing as highly strategic. Service models devolved from strategic partnerships to contracted suppliers. Technology advances necessitate a look back to the more client-centric, strategic, flexible models of the past.

INTRODUCTION

The dynamics of corporate real estate (CRE) global outsourcing trends have remained relatively consistent over the past decade. The top global trends advanced slowly and progress remained steady. For example:

• Investment and advances in technology and reporting;

• Programmes for human experience;

• Stakeholder engagement and customer relationship management (CRM) for the attraction and retention of talent;

• Customer loyalty and net promoter score (NPS) measures;

• The focus and requirements for compliance and risk mitigation;

• Process improvement is driven by client corporate business objectives;

• The opportunity to advance business transformation and innovation through process and service provider delivery improvements.

The pandemic consumer experience has also raised expectations of business post-pandemic to continue to be more socially responsible.

‘Probably the more relevant and pressing question is not about whether to invest in CSR or not, but more about how to invest in CSR to achieve the mutually beneficial and interdependent social, environmental and economic goals… Therefore, we can envision the post-pandemic period as a one that the thriving businesses are those with strong CSR commitment and effective CSR strategies and efficient implementations. Greenwash, pink-wash, and lip service will no longer survive closer consumer and public scrutiny.’2

INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

The reasons, approach, purpose and structures for CRE outsourcing are as varied as the organisations, industries and port- folios that deploy outsourcing. There are many outsourcing models in place for CRE services such as FM, project management (PjM), portfolio occupancy strategy and workplace management (PM), transactions management (TM) and consulting. As the major real estate service providers for CRE outsourcing services are global or regional to a large extent and the execution of PjM, PM, TM and consulting are typically transactional in frequency, the scope, service level agreements (SLAs) and nature of these services are not as fragmented as that of the FM global outsourcing industry.

FM outsourcing is highly fragmented for several reasons: definition, geographic, historic and cultural differences, access to FM training and education, the plethora of FM associations (by country), local employment laws, etc. The most basic and major divide for FM, however, lies with definition and the difference between integrated facility management (IFM) and facility services (FS). It is not unusual for consumers to consider all FM as tactical and perfunctory. With advances in technology within both IFM and FS, the services are quite advanced but as differentiated as the core businesses from which they have evolved. The foundations for IFM and FS respectively relate to the industries from which they are based. For example, IFM outsourcing began in the late 1980s in the commercial real estate industry. FS outsourcing began in the early 1900s in the US, UK and Europe and evolved in various regions of the world from companies such as ABM, ISS and which first started by providing janitorial, security, mechanical and electrical maintenance and repair services to building owners, tenants, the military and government. Subsequent decades saw growth and expansion in this sector in the US, Canada, UK, Europe and Asia Pacific with companies such as Service Master, JCI, Sodexo and United Group. These companies focus on the large-scale employment and performance of as many FS as possible from cleaning, janitorial, food service, landscaping, pest control, reception, repairs and maintenance, window cleaning, etc. The term total facility management (TFM) is used for FS companies that can ‘self-perform’ versus subcontract the majority of these services. The focus of TFM is the large-scale employment and broad self-performance of facility services.

Adapting the model promoted by Drucker, these companies created respect and career opportunity for outsourced facilities employees in the emerging profession of IFM. The contracting model was that of commercial property management where the service providers acted as a managing agent to provide outsourced corporate property management for the corporation’s owned and rented facilities. The IFM service provided was one of strategic investment asset management, looking at considerations such as location, tenant relations and business unit satisfaction, workplace occupancy and cost allocations, property value, process improvements, occupancy strategy, capital improvement planning, detailed financial reporting/benchmarking and view to the total cost of occupancy. Compass was sold

in the mid-1990s to Lend Lease and then ultimately to JLL, where it became the foundation for JLL’s corporate solutions business, Premisys was sold by Prudential Financial to Cushman & Wakefield to seed its national corporate occupier business, and TCC was sold to CBRE, launching the rise of the three largest real estate services providers in IFM and CRE by the early to mid-2000s.

‘FM appears to have spread into the industry in a short space of time i.e. within the last 40 years. The divergence of its definitions has been so rapid that it may not have firm root or might have been defined according to the originator’s taste, surrounding, and demographics at that point in time.’5

DEMAND SIDE DRIVERS

In response to the global pandemic, CREM leaders have been working hand in hand with the executive leadership of their organizations to respond strategically, empathetically, quickly and resourcefully. They have charted a safe, sustainable way forward through responsibly demonstrating leadership and knowledge. The confluence of issues the pandemic has brought to the fore is also changing the priorities of both the business and CRE in a way that is more aligned today than ever before. The awareness of the capabilities and profound impact that ‘space and place’ have on brand awareness, image, business productivity, health and safety, human experience, stakeholder engagement, suppliers, the environment and the local community has created a keener awareness of the importance of the function.

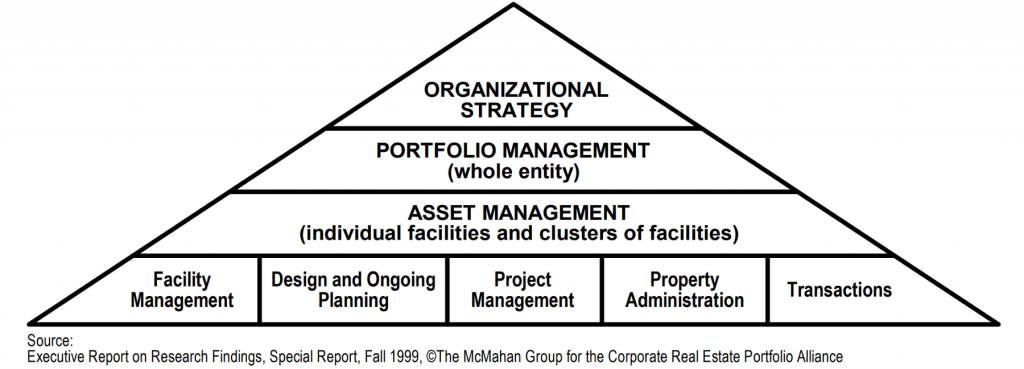

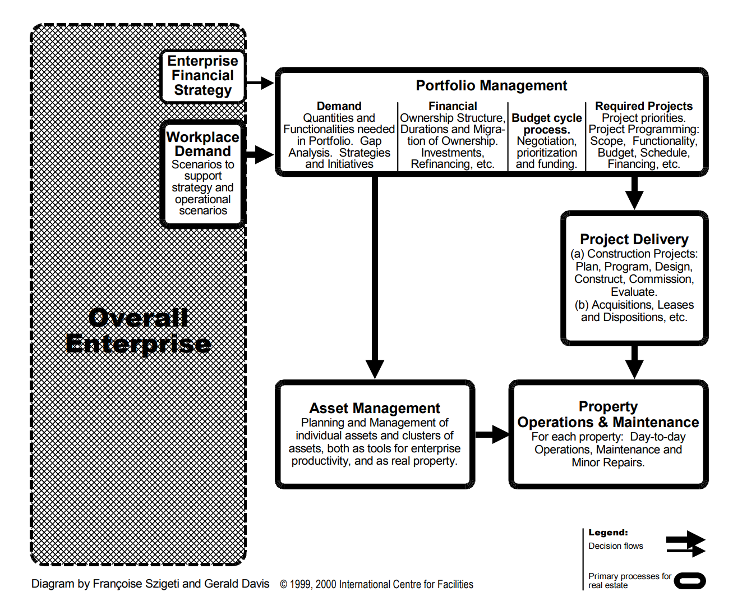

Figure 1: Corporate view of portfolio management, asset management and subordinate operating functions predicted for the future in 1999

Source: The McMahan Group for the Corporate Real Estate Portfolio Alliance8

‘In Figure 1, portfolio managers provide infrastructure to support organizational strategy. They give financial direction to asset managers who are in charge of major individual facilities and clusters of facilities. Facility management is seen as one of the technical operating functions that support portfolio and asset managers. This diagram presents the perspective, in the spring of 1999, of some unusually thoughtful, forward-thinking, high-ranked real estate executives.’9

They envisioned CRE playing a similar role to that of an investment asset manager and fiduciary adviser in commercial real estate. Figure 1 is more relevant today than it had been, as it took time for the enterprise acceptance of the profession to move from ‘cost centre to ‘value creator’. In part, that progression has been ignited by the confluence of strategies required to address the heightened need to implement environmental, social and governance goals for which the CRE plays a contributive role.

Over the past decade, typical property cost reduction measures have ranged from downward pressure on space size to deliver small, open, efficient workstations, running equipment to fail, reducing fresh air intake to save on energy bills, reducing cleaning specifications and routine cleaning protocols, seeking FM outsourcing suppliers which can self-perform a very broad scope of work with employees under one employer (reducing the number of small and local suppliers), vendor supplier consolidation rather than contracting with multiple suppliers with required collaboration and sharing of resources and technology. As cost reduction has historically been the primary focus of attention, a stark contrast is now revealed in new requirements for social distancing, space cleanliness for health and safety, increased fresh air intake for healthier space and collaboration among suppliers to solve for challenges of accessing supplies, sharing data and information, creating opportunity for small suppliers in local communities due to a stressed supply chain. These are some examples of the change which is requiring innovation and rethinking how to gain efficiency and to provide and consume space differently using alternative protocols and delivery models. One lesson learned during the pandemic is the acceptance and willingness of employees, companies and the community to come together and adapt readily to change for the greater good and to help one another. From this we have learned that human experience remains very important, but what employees and the public also expect as an experience is authentic and socially conscious behaviour.

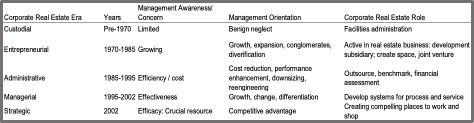

Figure 2: Evolution of CRE emphases up to 2002

Source: Roulac11

CREM research over the past 20 years has been tracking the advancement of CRE becoming considered core and integral to business purpose and execution.

‘The places in which a company’s facilities are located and the specific spatial attributes of those facilities define and reflect its culture. Since places and spaces shape behavior of executives, employees, and customers, the decisions about the implementation of the enterprise’s corporate real estate strategy are ultimately decisions that reinforce and shape the organization’s culture.’12

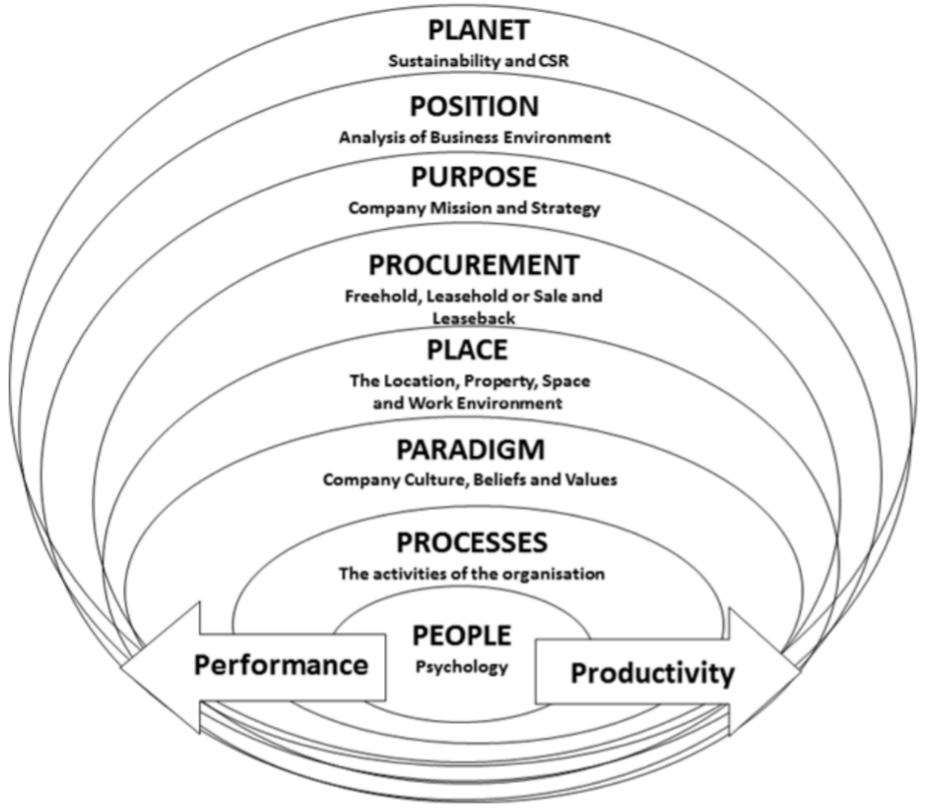

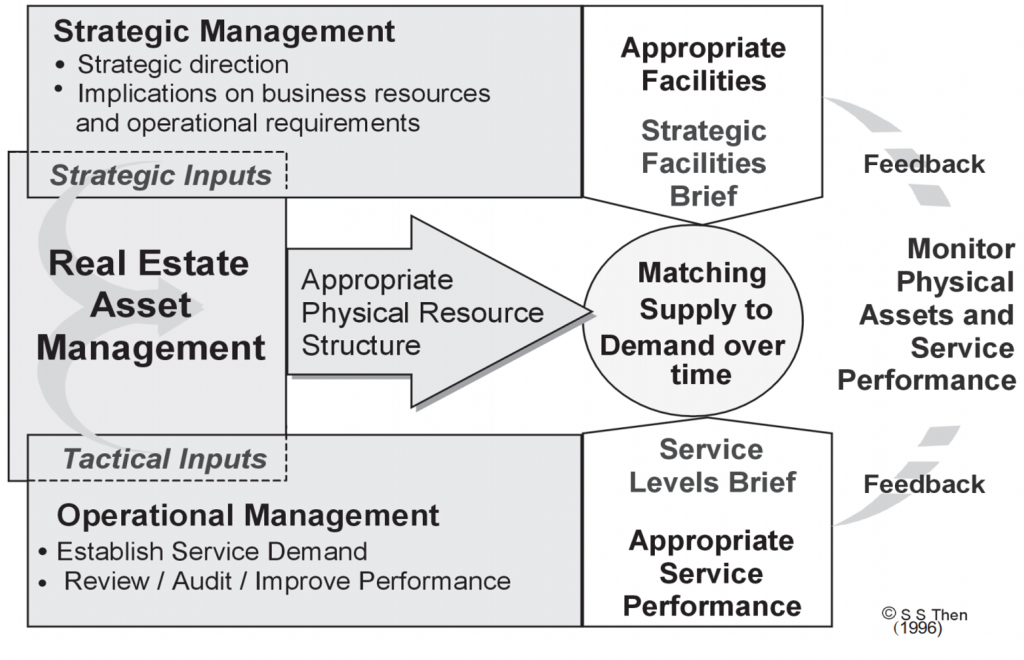

Figure 3: CRE asset management alignment model

Source: Langford and Haynes13

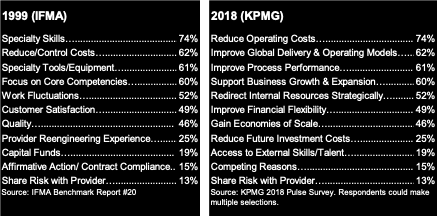

Figure 4: Why companies outsource

Source: IFMA/KPMG17

The 2018 survey results support research conducted by Roulac which concluded that,

‘CRE corporate property strategy impacts and produces positive outcomes in employee satisfaction, production factor economics, business opportunities realized and forgone, risk management considerations, and other impacts on enterprise value. These consequences enhance or detract from business outcomes — specifically management’s ability to add value to increase shareholder wealth.’18

The shift in priorities exemplifies the progress and value enhancement gained through the maturation of IFM as a strategic service offering. A similar fundamental shift has also occurred in FS due to cost savings, technology, and process automation and enhancements.

Lessons are being learned rapidly that span the pandemic response to social unrest which now challenges the way we work, think, behave and prioritize. The response from business ecosystems to these factors will influence how organizations are regarded as externally and internally driving new strategic imperatives. One such outcome is the embrace of real estate/IFM as a strategic management function where the trend to remain or take more in-house is gaining momentum (see Figure 5). In-house CREFM teams will self-perform functions seen to be fundamental to the core business or choose to bring technology, CRE and FM data, energy management, workplace occupancy strategy, asset management and other services back in-house to ‘insource’ or ‘backsource’ a process or function that had been previously outsourced. Roulac’s research supports this emerging trend, as ‘the development of a CRE alignment model has become a business imperative for the in- house CRE team where the CRE strategy delivers added value and enhanced organizational performance’. His research ‘presents the case for the existence of significant contributions to enterprise value by means of superior corporate property strategies by citing the contribution of corporate property/real estate to enterprise competitive advantage through creating and retaining customers, attracting and retaining outstanding people, contributing to effective business processes to optimize productivity, promoting enterprise values and culture, stimulating innovation and learning, enabling core competency and increasing shareholder wealth.’19

These shifts in the demand side of CREFM are only now gaining traction due to advances in technology. The advances have created outsourcing models that are based on managing agents and hybrid models that leverage AAS platforms. Additionally, with the mandate for change and achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs), customers will be looking to implement new structures for service delivery models to improve environmental impact (reduce greenhouse gases [GHG]), improve health and safety protocols, diversity and inclusion of small local and regional suppliers, shared technology, infrastructure and shared economy delivery models and to enhance innovation, agility, flexibility and partnerships while significantly reducing cost and adding value.

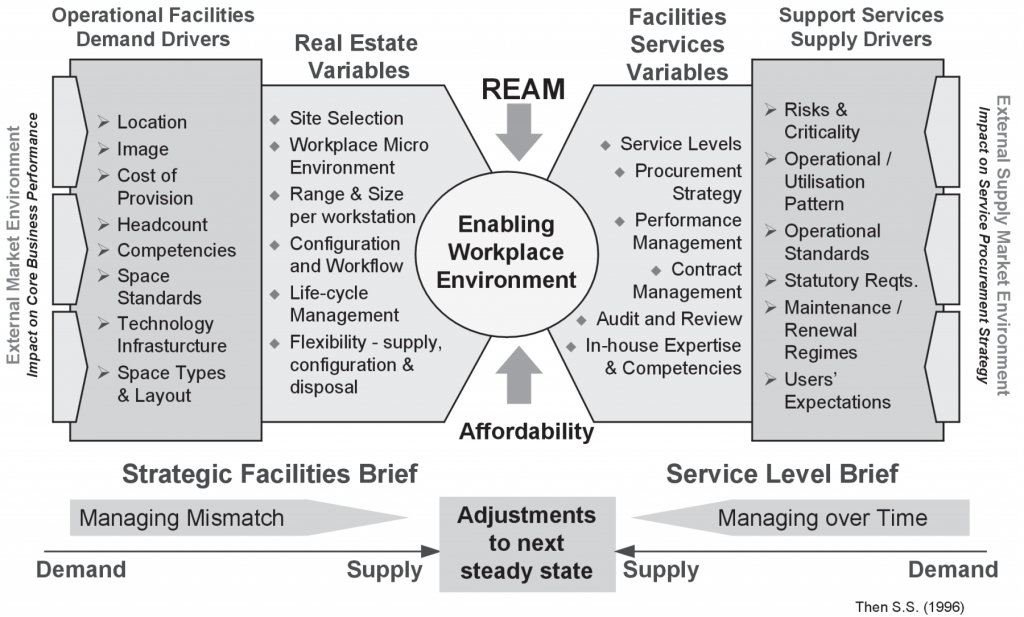

Figure 5: Justification for real estate asset management (REAM) as an integrating function

Source: Then20

The demand side models for CREFM outsourcing are adapting quickly to rethink internal functions and the new role of the in-house team and technology platforms and the power of data. Haynes cited in his research:

‘The prospective payoff of superior corporate property strategy is enormous. Superior corporate property strategies promote multiple objectives of strategic advantage, innovation, business growth, productivity, human resources, business profitability and wealth creation. Superior corporate property strategies enhance the enterprise’s competitive advantage and core competencies by creating and retaining customers, attracting and retaining outstanding people, contributing to effective business processes to optimize productivity, promoting the enterprise’s values and culture, stimulating innovation and learning, and enhancing shareholder wealth.’23

Figure 6: REAM as managing the enabling workplace environment

Source: Then22

The delivery of corporate property strategy objectives is supporting the enterprise in realizing this potential. While the potential has been seen for many years, the realization of the vision is due to dynamic change in real estate technology platforms and the leverage and data created by them which promotes flexibility, SDG, scale and efficiency.

SUPPLY SIDE DRIVERS

FS and TFM companies seek to provide large scale, self-performance and direct staffing of a large range of services from cleaning/janitorial, security, food services/catering, landscaping, business/mail and support. Focused on vertically self-delivering upon the scope of a broad service for businesses and properties, the revenue for these firms has historically been reported on a gross basis as their fees are based upon the staffing, services or work performed as well as the provision of equipment, supplies and materials that accompany the service. The number of employees for these FS/TFM companies can range up to 500,000+. The companies in this sector are considered primarily hard or soft services providers specializing at their core, for example, in engineering/ repairs and maintenance, energy management, catering, cleaning, security or business services. Analyst coverage on the publicly traded firms in this sector considers the size of the contracts, self-performance scope, employee headcount, contract risk, growth and margin performance. Pressure on a year- over-year gross revenue growth has led many FS/TFM companies to pursue horizontal expansion. Unfortunately, a double-edged sword prevails with analyst concerns over loss of focus away from core activities (perceived strengths such as catering, cleaning, maintenance, security or business services) and contract risk (lack of expertise, losses, penalties), untested market sectors (to secure future growth potential) and margin erosion.

IFM real estate providers have now had experience in several generations of outsourcing contracts and models, from the early managing agent models to fixed price and guaranteed maximum price contracts and the shift to assuming principal risk for the vertical services provided by subcontractors. Outsourcing conversations with customers over the recent past often centre around decision making, control and accountability, outcome-based contracts, glide path savings, performance management, cost avoidance, facility conditions deterioration and a desire for more transparency and operational input/control. The contracting model has centered around operating expense management. The shift to space and occupancy strategy, capital lifecycle planning, operational excellence, innovation, customer experience as well as cost optimization all enabled by integrated technological solutions for the provision of business intelligence has necessitated a different approach to FM contracting and supplier partners.

Contemporary outsourcing seeks advanced partnership, collaboration, global service consistency, investment and increased flexibility and agility. As real estate companies in real estate/IFM are focused on value creation, partnership, cost reduction, compliance, transparency and customer experience, their expertise and innovation in their products, platforms and technology provides differentiated service and expertise which incorporates hard and soft services delivery into a more comprehensive delivery model. These companies have invested heavily in self-delivery of services, technology, process improvement, creating scale and leverage and measuring total cost of occupancy. CREM research over the past 20+ years has focused on the need for CREM to integrate real estate with FSM and implementing the asset management model. This approach has gained momentum in real estate investment trusts (REITs) and some internal CRE property management/asset management models, but overall, the role of asset manager in IFM has not made progress until recently, given the change in priorities of CREM organizations. Business transformation, major progress in property technologies, outcome- based models, digitization of automated workflows, employee experience and personalization of space AAS are all drivers that suppliers can provide in an aligned, strategic, sustainable partnership. Advanced organizational models and a deeper focus on programming to reflect customer core values and driving CSR goals support the case for asset management to oversee the facilities’ maintenance and services function.

Portfolio management is the link in the value chain between real estate and facility operations and core business decisions, values and finances of an enterprise. Portfolio management decides what workplaces should be in the portfolio and what projects are needed to get the right mix in the right places. Projects may be to dispose of property or to acquire it; to build, buy or rent; or to finance or rehabilitate it. The CRE alliance of thought leaders defined portfolio management as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7 shows how portfolio managers provide infrastructure to support organizational strategy. They give financial direction to asset managers who are in charge of major individual facilities and clusters of facilities. FM is seen as one of the technical operating functions that support portfolio and asset managers. Figure 7 presents the perspective, in the spring of 1999, of some unusually thoughtful, forward-thinking, high-ranked real estate executives. The vision, now being realized in 2020, required a change in circumstances, priorities and the perceived value and objectives of CREFM.

Portfolio management brings together real estate managers and financial managers to develop the strategy for the real estate portfolio and related financing. They draw on information about core functions of the enterprise as they manage the real estate strategy for providing physical workplaces for the enterprise, and the financial aspects. Together, the team of portfolio managers takes direction from the business units and identifies projects and budgets to meet workplace needs. Portfolio managers also ensure that the portfolio as a whole meets the current and future needs of the enterprise. This is a crucial part of the value chain in support of the enterprise.

Asset management is a function that manages individual assets. Facility by facility, it is responsible for each real property asset, or cluster of assets such as a campus, operating within the framework set by portfolio management. It periodically updates the asset management plan for each property used by the enterprise. Each asset manager is the advocate for projects for their property and gives general direction to property operations and maintenance.

Figure 8: Leading trends in CREFM

Source: Author

LEADING TRENDS IN CREFM ARE DRIVEN BY THE BUSINESS TRANSFORMATION OBJECTIVES OF THE ENTERPRISE

(1) Impact, SDGs and ESG: The imperative for change, stakeholder scrutiny of an organization’s purpose, demand for transparency and accountability and ESG measurement criteria of the sustainability and societal impact of socially responsible or ‘green’ investing are propelling the acceleration of the trends as well as fundamental shifts in the supply and demand models for CRE outsourcing.

‘Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria are a set of standards for a company’s operations that socially conscious investors use to screen potential investments. Environmental criteria consider how a company performs as a steward of nature. Social criteria examine how it manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates. Governance deals with a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights.’25

The impact an enterprise has broadly on its stakeholders, the community, environment and society, clearly articulating its purpose and commitments and holding itself accountable has become a major area of focus for business in striving to meet the 2030 deadline the United Nations has established for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2030 SDGs have emerged as a public policy goal in response to unprecedented climate change, increasing industrialization, population growth and widening inequalities;

(2) Globalization and business transformation: Both have been a trend and imperative for businesses to expand into other markets, increase revenues and grow. The global economy integrates people, companies and governments.

‘A volatile world of partially connected national economies expands possibilities for global strategy even as it complicates the management of multinational firms. Now is the time for global corporations to show their value by harnessing the best of the world’s capabilities to end the pandemic and bolster the recovery.’26

As customers and suppliers have become more global, globalization has become an increasing priority for real estate and FM service firms. Serving a customer that is truly global in a consistent way across multiple national offices presents challenges that technology, advanced supply chain strategies and shared economy approaches help to solve;

(3) Human experience: Economic progress has moved the service economy to the experience economy where environments and experiences are intentionally created for customers, employees and other stakeholders in a personal and memorable way. Human experience which is being augmented by technology and the IoT is being used by companies to create deeper connections while fostering loyalty within their relationships and drive overall growth as a measure of success. Human and employee experience are fundamental to the business and CRE. The curation of experiences is part of innovation where continuous improvement moves the business further away from simply providing goods and services;

(4) Digitization, transparency, business intelligence (BI) and artificial intelligence (AI): In an era of expanding technology and AI, the human aspect of business has become more prevalent than ever before. Digital transformation enables the organization to deal better with change overall, essentially making change a core competency as the enterprise becomes customer- driven end-to-end. The need and desire for agility are facilitating ongoing digital initiatives. Digitization of end-to-end processes streamline data consistently and methods of delivery. It promulgates ever-improving standards and improves business intelligence supported by AI. The business must digitize information, process roles that make up the operations of a business which will digitally transform the business and its strategy and help to make the business more resilient and transparent;

(5) Managing/mitigating risk and compliance: Core components of corporate social responsibility, ensuring the health of the business and protecting the stability and resiliency of the organization and the brand for its stakeholders. Quality assurance, business standards, globalization and technology trends are all driving business transformation which brings with it both unprecedented risks and opportunities. The business is therefore required to combine innovation and risk management to create comprehensive risk compliance programs that both seize on opportunities while meeting stakeholders’ expectations. As CRE continues to become part of the core business through business, experience and digital transformation, the trend toward transparency and compliance, predictability and consistency is a key component of CRE planning, execution and audit;

(6) The shared economy and the opportunity: Creates present significant benefits to CRE and real estate/IFM for creating leverage while reducing GHG emissions, buying locally, creating more opportunities for inclusion of small, local, regional and diverse suppliers having a positive societal, economic and community impact. Additionally, through the use of technology to create scale and consistency, small suppliers can be part of the supply chain eliminating the dependence on large FS/IFM companies to reduce the number of vendors the company is working with. Shared economy models promote innovation, economies of scale in a new format and inclusion of the cloud workforce. ‘The premise of the shared economy is that parties, through an online shared marketplace, collaborative platform, or peer-to-peer application, share value from an underutilized skill or asset.’27

The shared economy is gaining momentum through digital FM plat- forms because of the flexibility, agility, diversification, scale, best-in-class local service and detailed data it aggregates and measures. The shared economy is estimated to grow from US$14bn in 2014 to US$335bn by 2025.

‘What’s fascinating is that the company is rarely the actual service provider; instead, they act as facilitator, making the transaction possible, easy, and safe for both the provider and the user. They break down the barriers that otherwise exist to starting a business or a “side hustle” for many people or companies and make it both easy and lucrative to participate in this collaborative economy.’28

(7) Diversity and inclusion: Social awareness has driven employers to ensure equality and equity initiatives for compliance obligations and to increase the overall bottom line with a more diverse workforce and supplier partner base. Aside from legal requirements, companies are beginning to implement designs in their workspaces that can accommodate stylistic ways of working for everyone as well as the mental, emotional and physical health of their employees. This includes accommodating work/life balance, eg providing on-site childcare, comfort and quiet zones, amenities and variability and practicality of design that can encourage and accommodate employees in a thoughtfully inclusive environment.29 To meet consumer expectations for CSR companies are targeting to decrease waste and emissions, work with greater efficiency and increase the participation of diverse suppliers in their supply chain. A commitment to ethical procurement practices is important to company shareholders, consumers, employees and the local communities where these practices make an impact;

(8) Environment, climate change and CO2 reduction: GHG reduction and environmental ecosystem destruction must be systemically addressed to flatten the curve for global climate change. Accelerated sea-level rise, longer, more intense heat waves, the loss of sea ice, water scarcity, severe storms and disease spread are some of the issues that threaten health, infrastructure and economies. ‘Risk mitigation, brand enhancement and talent and customer attraction and retention are tangible and positive by-products of corporates doing the right thing by adopting greater sustainability measures’30;

(9) Flexibility, agility and innovation: Foundational in the way business and leadership build capacity for the organization to thrive in an era of ‘always on’ transformation and change.

‘Organizational agility is the ability to rapidly adapt while delivering innovation and customer-centric strategies. It is increasingly recognized as key to enduring success. Agility goes beyond being flexible. A flexible business is able to make changes within the current organizational system when a predicted event occurs. Agile businesses are able to change the overall system completely in response to an unpredictable external force.’31

Enterprise is actively placing the principles of agile resilience throughout the organization to anticipate, focus, iterate, learn, collaborate and persevere requiring new ways of thinking, working, partnering and being. The need to rapidly change can be accomplished by creating new business models to disrupt, propel and advance. By linking the new technologies which are available to CRE with the emerging market needs, transformation and change will occur. Value is created and captured by defining the customer value proposition, the pricing mechanism and structuring the supply chain.

‘In any given industry, a dominant business model tends to emerge over time. In the absence of market distortions, the model will reflect the most efficient way to allocate and organize resources. Most attempts to introduce a new model fail — but occasionally one succeeds in overturning the dominant model, usually by leveraging a new technology. If new entrants use the model to dis- place incumbents, or if competitors adopt it, then the industry has been transformed.’32

(10) Operational excellence, resilience and business continuity planning: Critical to ensure predictable and reliable business outcomes, cost avoidance, quality assurance and optimal asset life cycle capital planning. Business continuity and emergency response planning for critical environments are fundamental to mitigate potential business upsets. Therefore, operational excellence addresses challenges that extend beyond business-as-usual (BAU) circumstances — processes and emergency response processes must be managed efficiently so that responses can be timely in unexpected circumstances. Business continuity planning creates a system within operations protocols which includes plans to get back to BAU operations as soon as possible immediately following an unprecedented event or interruption. Planning for resiliency and eliminating operational downtime with processes, carrying parts or supplies on hand, training, procedures, lessons learned from past events provides more resiliency and risk mitigation for the organization.

MAJOR TRENDS ARE DRIVING A SHIFT IN PRIORITIES AND NEW OUTSOURCING MODELS

Emerging market needs have created a delineation in the differences in priorities and core competencies of suppliers. Technology has driven the ability to introduce automation and platforms which disrupt and respond to market demand. The most efficient and effective way to allocate and organize resources today is necessitating a change in the traditional CREM outsourcing model. Six keys to success cited in CREM outsourcing transformation are a more personalized service, closed-loop process, asset sharing, usage-based pricing, a more collaborative ecosystem and an agile and adaptive organization.33 CREM has seen a shift in the importance of integration of a diverse set of disciplines and the corresponding data, workflows, underlying systems, compliance and an uncompromising demand for subject matter expertise.

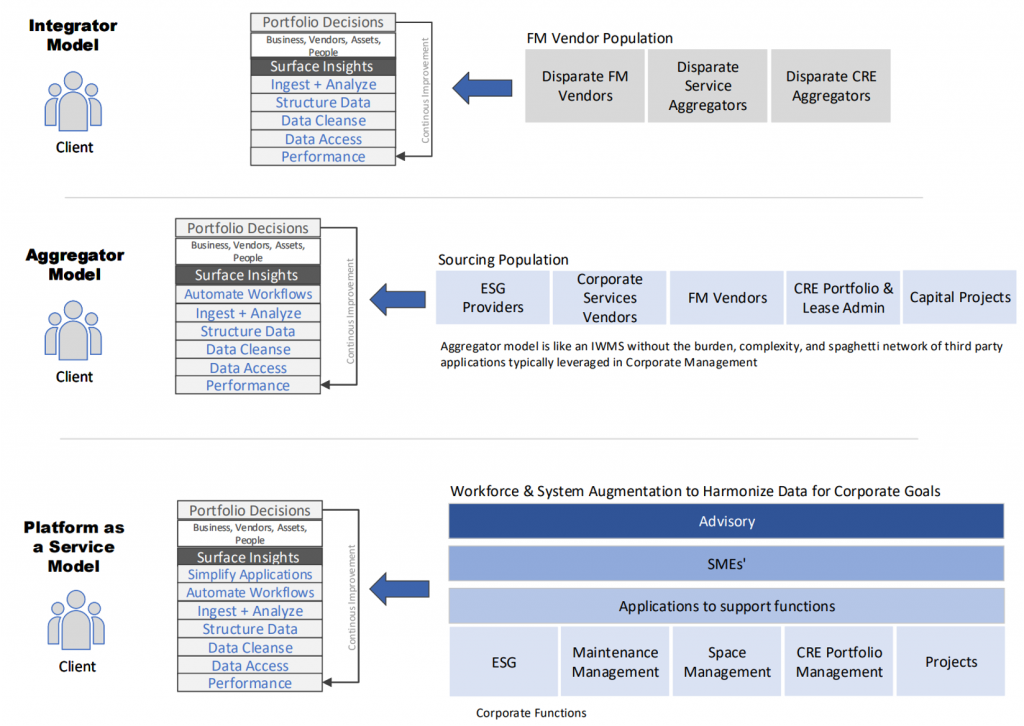

The new role of an asset manager/ managing agent to act as an owner’s representative to support CREM portfolio management ‘integrator’ standardizes service provider process flows, establishes data and operating standards, communicates changing business priorities, aggregates performance reporting, eliminates duplication within multiple account teams and provides advanced technology to create an operating environment which challenges the dominant business model. Technology has enabled a shared economy model and is increasing business segment entrants to manage AAS technology platforms of scale and quality. The need for optionality and more control is giving rise to the desire to insource, backsource and retain real estate/FM functions in-house. Establishing an outsourced, strategic asset manager/agency model accelerates business transformation by delineating between platform, process and infrastructure and day-to-day facility services procurement. Major trends substantiate the rationale to divide outsourced service delivery between strategic platform and services delivery. By separating the platform separately from hard and soft service contracting, this results in an adaptive organizational model. This trans- formative model enables an internal group or outsourced asset manager to establish a world-class, single infrastructure from which to operate eliminating redundancy of reporting, account support teams, etc., and subcontracts with the best local FS suppliers for catering, cleaning, repairs and maintenance, security, business services placing incentives and performance/contract risk where most appropriate.

The real estate/IFM service providers have the expertise and leading systems to provide the asset management function to CREM. By establishing the desired platform infrastructure, reporting, oversight and programming, the model also helps to solve the challenges of globalization and self-delivery challenges. A shared economy model over- turns the dominant model and propels the industry to provide much-needed flexibility, automation, data and business intelligence. Resiliency, risk mitigation and speed to change out non-performers are creating a necessary paradigm shift in the industry that requires a new dialogue and understanding of the potential of digital AAS platforms.

CONCLUSION

The managing agent model for IFM was utilized by CRE during the first decade (1989–99) of strategic IFM outsourcing. The model coexisted alongside the principal risk model in use with FS companies with which the managing agents or in-house teams subcontracted. By the end of that decade, academics and real estate thought leaders were predicting an elevated, more strategic asset management/advisory partner role for IFM. An example of the model can be found in the Microsoft case study in Vitasek’s The Vested Outsourcing Manual: A Guide for Creating Successful Business and Outsourcing Agreements.34

Due to the lack of clarity between the role of IFM and FS, procurement practices for commodity services, nascent technology, process compliance and quality assurance constraints, recessions and recovery periods which ensued from 2000–20, led the dominant outsourcing model to become one of extreme self-performance, savings guarantees and large, principal risk contracts (see Figure 9). The change in accounting standards that require the real estate IFM providers to record pass-through spend as revenue has had an impact on the pricing, profit margins and the risk profile of the IFM business. To manage risk and margin impact, the contracts now have increased payroll burden rates, more pass-through on expensive corporate platform costs and mark-ups of various bundled services that had previously been charged at cost.

Figure 9: New outsourcing models distinguish between advisory and tactical execution

Source: Blue Skyre IBE

CRE today is looking for improved cost transparency, data standards and consistency, accessible business analytics and business intelligence, innovation and advisory on strategic initiatives, digital processes to drive leverage, reduced inefficient costs of provider platform charges and streamlined and managed tactical delivery of services. Additionally, fueled by a mandate for ongoing business transformation, CRE has aligned with the core business responding to leading business trends.

As the CRE outsourcing industry advances and evolves over the next several years, it will be recognized more broadly for the critical importance CREM plays to enable the core business in optimizing outcomes. The new unambiguity and value clarity of different outsourcing delivery models (IFM, TFM/ FS vs strategic asset managing agent), access to advanced, open tech-enabled (aggregator and AAS) platforms, emphasis on advancing SDGs/ESG and service innovation is bringing higher-value CRE strategic service delivery models to market. The new models focus on a pragmatic approach to operations, technology and data management. This approach understands the importance of acting and reporting globally as well as locally through end-to-end automated processes to enable experience, SDG attainment and reporting relevant, detailed site data.

The market shifts benefits both CREM in-house teams as well as service providers. The ability to go narrower and deeper to focus, improve and excel on local, tactical core service delivery, differentiates, improves performance, reduces cost transparently and allows for speed in transformation. Adapting shared economy models for delivery of tactical services and processes provides flexibility to quickly change out non-performers in a ‘plug-and-play’ format to improve resiliency and operational consistency. The desire for providers to ‘self-perform’ all services everywhere will change due to: 1) advanced technology platforms; 2) the requirement for better alignment between strategic objectives; and 3) to be more responsive/flexible to the changing needs of the business.

An asset management/managing agent digital platform model allows the engagement of suppliers based on delivery strength by property type and market in a leading, inclusive, standardized, efficient, integrated service model. This model eliminates costly platform redundancies, engages the best-in- class local provider(s), creates opportunity, places principal risk at the point of delivery, reduces cost, improves environmental impact and leverages remote operations centers for more automated, digital service delivery and smart buildings/IoT experiential implementations.

A digital platform harmonizes the data collected from the multiple providers and delivers it in sufficient detail to satisfy several objectives: provide business leaders with the critical insights they need to optimize their operations at the site level, improve execution of strategy across the portfolio among the providers, facilitate sharing of best practices among providers, and measure the overall effectiveness of the FM team’s contribution to the enterprise’s goals for cost savings, operational efficiencies, resiliency, diversity and ESG impact.

In 2020, advanced technology provides the platform to realize the potential of the managing agent — the strategic adviser role envisioned 20 years ago. Fit-for-purpose automation and data ecosystems, standardization, access to real-time business analytics and intelligence is realizing the promise of digital FM and IoT. As in Back to the Future,35 the asset management models being pro- posed in 1999 meant as much to CREM as the ‘flux capacitor’. Today technology and requirements for the strategic, elevated role of CREFM have entered the zeitgeist.

REFERENCES

(1) Hammond, K. (April 2020), ‘Global Outlook 2020: The Quest for Growth Amid the Turmoil’, Pulse Central, available at iaoppulse.net/global-outlook-2020/ (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(2) He, H. and Harris, L. (2020), ‘The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Philosophy’, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 116, pp. 176–182.

(3) KPMG (July 2020), ‘CEO Outlook: COVID-19 Special Edition’, available at home.kpmg/xx/en/ home/insights/2020/08/global-ceo- outlook-2020.html (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(4) Drucker, P. F. (November 2005), ‘Sell the Mailroom’, Wall Street Journal, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/ SB113202230063197204 (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(5) Nor, N. A. M., Mohammed, A. H. and Alias, B. (2014), ‘Facility Management History and Evolution’, International Journal of Facility Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 1–21.

(6) ISO (August 2018), ‘ISO 41001:2018 – The World’s First International Facilities Management System (FMS) Standard’, Pegasus, available at https://www. pegasuslegalregister.com/2018/08/03/ iso-410012018-worlds-first-international- fms-standard/ (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(7) Szigeti, F. and Davis, G. (2020), ‘The Value Chain for The Value Chain for Corporate Real Estate’, International Center for Facilities.

(8) The McMahan Group for the Corporate Real Estate Portfolio Alliance (Fall 1999), ‘Executive Report on Research Finding’, Special Report.

(9) Ibid., note 7.

(10) Roulac, S. (2001), ‘Corporate Property Strategy is Integral to Corporate Business Strategy’, Journal of Real Estate Research, Vol. 22, pp. 129–152.

(11) Ibid., note 10.

(12) Ibid., note 10.

(13) Haynes, B. (2012), ‘Corporate real estate asset management: Aligned vision’, Journal of Corporate Real Estate, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 244–254.

(14) Ibid., note 13.

(15) International Facility Management Association (1999), ‘Outlook on outsourcing’, Houston, Texas.

(16) Lepeak, S., Gilles, P., Burr, D. and Fairbanks, C. (2019), ‘2019 Global Real Estate and Facilities Management (REFM) Outsourcing Pulse Survey Results’, KPMG, available at advisory. kpmg.us/content/dam/advisory/en/ pdfs/2019/2019-refm-outsourcing-pulse- slide-deck.pdf (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(17) Ibid., note 15; Ibid., note 16.

(18) Ibid., note 11.

(19) Ibid., note 11.

(20) Then, D. S-S. (2005), ‘A proactive property management model that integrates real estate provision and facilities services management’, International Journal of Property Management, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 33–42.

(21) Ibid., note 11.

(22) Ibid., note 20.

(23) Ibid., note 13.

(24) Ibid., note 17.

(25) Chen, J. (March 2020), ‘Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria’, Investopedia, available at https://www. investopedia.com/terms/e/environmental- social-and-governance-esg-criteria.asp (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(26) Altman, S. A. (June 2020), ‘Will Covid-19 Have a Lasting Impact on Globalization?’, Harvard Business Review, available at hbr.org/2020/05/will-covid-19-have-a-lasting-impact-on-globalization (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(27) Naeemullah, I. (2020), ‘Factors to Consider in Commercial Shared Economy Leasing’, American Bar Association, available at https:// www.americanbar.org/groups/real_property_trust_estate/publications/ probate-property-magazine/2020/ march-april/factors-consider-commercial- shared-economy-leasing/ (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(28) Marr, B. (2016), ‘The Sharing Economy – What It Is, Examples, And How Big Data, Platforms And Algorithms Fuel It’, Forbes, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2016/10/21/ the-sharing-economy-what-it-is- examples-and-how-big-data-platforms- and-algorithms-fuel/#5e7034847c5a (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(29) JLL (March 2020), ‘How Companies Are Designing Spaces That Promote Inclusivity and Equality’, available at https://www.us.jll.com/en/ trends-and-insights/workplace/ how-companies-are-designing-spaces-that- promote-inclusivity-and-equality (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(30) JLL (March 2020), ‘How Gen Z and Millennials Are Putting Sustainability on Corporate Agendas’, available at https://www.us.jll.com/en/ trends-and-insights/workplace/ how-gen-z-and-millennials-are-putting- sustainability-on-corporate-agendas (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(31) Holbeche, L. (August 2018), ‘Agility and Flexibility Aren’t the Same’, Home, available at https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/agility-and-flexibility-arent-the-same (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(32) Stelios K., Ladas. K. and Loch, C. (February 2018), ‘The 6 Elements of Truly Transformative Business Models’, Harvard Business Review, available at hbr.org/2016/10/the-transformative- business-model (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(33) Adhikari, D. D., Hoffman, S. and Lietke, B. (November 2019), ‘Six Emerging Trends in Facilities Management Sourcing’, McKinsey, available at https:// www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/ operations/our-insights/six-emerging- trends-in-facilities-management-sourcing (accessed 28th September, 2020).

(34) Vitasek, K. (2011), The Vested Outsourcing Manual: A Guide for Creating Successful Business and Outsourcing Agreements, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

(35) Zemeckis, R. (dir.) (1985), Back to the Future, Universal Pictures.